By Ben Orlove, JCAN NYC steering committee member

I am glad to report back on my recent visit to COP28, the global climate conference held last month in Dubai. I am glad as well for all the interest that I’ve received from people who have asked me about my time there. I take that interest as a sign that people have not succumbed to climate anxiety or climate grief, but rather that they retain a sense that positive action on the climate crisis is still possible. That sense is one that I share. It’s a sense that animates JCAN as well.

Some people express pessimism about the COP process. They recognize the vast power of fossil fuel companies and fossil fuel producing countries, either because of their wealth and influence, or from the ability of any country at the COP to veto a proposal, since all resolutions have to be passed unanimously, with any of the 198 member countries having the option to exercise a veto.

At the COP, I got a sense that there are some limits to the power of the petrostates to block the process. When the head of the COP, who manages the state energy company of the host country, the United Arab Emirates, suggested that the use of fossil fuels could not be ended without impoverishing the world as a whole, he received a great deal of negative publicity, and had the embarrassment of organizing an emergency press conference to walk back his comments. It was also evident that the small island states, which all have votes, can speak powerfully as well.

A number of excellent summaries of the outcomes from this COP are available online. I recommend this summary from Carbon Brief as a place to start. And, to cut to the chase, I can report on the points that struck me as major takeaways:

Speaking directly about fossil fuels. The whole COP process began with an agreement “to achieve stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” So greenhouse gasses have been on the table from the start, and after some years, there was also agreement on temperature thresholds—keeping the warming below 2°C or close to 1.5˚C. But it has been a challenge to produce statements that would refer to fossil fuels. Recent COPs have spoken about a “phase down” of coal—a weaker phrase than the “phase out” many had sought. So it was an advance to have all fossil fuels mentioned at COP28, though “transition away” from them is quite vague.

Loss and damage. Small island states have been pressing since the late 1990s to set up funding and mechanisms to address the harms that countries are experiencing for which adaptation is not possible. This COP provided that effort with a major win—the launching of a fund for such compensation. Details remain unclear, but this is one step that cannot be walked back. This was another point I witnessed at the COP: the great respect given to small island states and other coastal countries, faced with impacts of sea level rise.

Financing. This issue remains a major ongoing point of contention. Poor countries have substantial energy needs, and they can’t meet them with renewable sources unless wealthy countries provide significantly higher levels of funding.

Overshoot. This word, used with increasing frequency in climate circles, is a way to deal with the fact that the world is barreling ahead to shoot past 1.5˚C and 2°C. This term suggests that the world could come back down from a higher temperature to one of the preferred levels, so that the period of exceeding the threshold would be finite—and hopefully brief.

Like most of the nearly 100,000 people who participated at the COP, I was not one of the official country delegates, able to cast a vote at the sessions at which the key resolutions were approved. I attended meetings at which representatives of different countries, NGOs and other civil society organizations provided testimony and offered comments on draft documents; I coordinated closely with an NGO that focuses on the negative impacts that come from letting polar ice sheets and mountain glaciers melt, including sea level rise, reduction of water resources, natural hazards and the harms of culturally significant landscapes. I also attended side events, where organizations gave talks. To convey some of the experience, I include some photographs from the COP.

This Indigenous Dayak woman from the Malaysian portion of Borneo brought these leaves from her home area, along with water from a river in a local forest. She is chanting a prayer as the opening invocation of the Indigenous Pavilion. She explained the significance of each of the three plants, and spoke of the importance of Indigenous spirituality within culture.

These two Indigenous Maasai leaders from Yanzania, pictured with me, spoke extensively about the importance of assuring Indigenous sovereignty in the transition to renewable energy. Some governments have built hydropower dams that flood Indigenous lands, or have simply usurped these lands to obtain ore for minerals, like lithium, cobalt and copper, required in batteries.

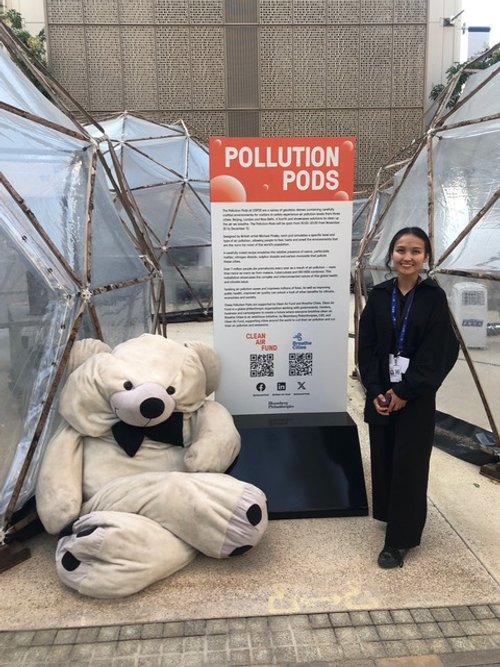

This young woman from Kyrgyzstan works with a communications NGO which constructs domes. Each of them contains air at a specific level of pollution corresponding to recent climate-related bad air days in specific locations around the world. The stuffed bear had been left outside for some weeks in Kathmandu, where its white cloth covering was darkened by soot. The more forceful demonstrations that have been a feature of many COPs were limited in number and scale because of the policies of the United Arab Emirates.

I have worked with this Indigenous Sherpa leaders from Nepal for several years. We discussed steps to promote full Indigenous participation in adaptation projects in mountain regions.

And there were others who I don’t have pictures of. A representative of a postal workers’ union in Canada, concerned about the impacts of wildfires on worker health in her country. A government official from Nigeria, who explained that the wealthy countries are not giving enough financing for his country to meet basic energy needs for health, education and food security through renewable sources. A Chinese woman, based in London, who serves as a simultaneous interpreter at the plenary sessions; she spoke of the challenges of coming up with terms in Chinese for “bottleneck” and “overshoot.” An official representative from Iceland (who can vote on resolutions) who spoke of the growing linkages between mountain, polar and coastal countries to provide a unified voice on sea level rise.

Meeting people like these, my hopes are renewed. The COP gave me the sense that there are many groups like JCAN, working on issues in their cities and communities and nations. We are not alone.